Fault Lines

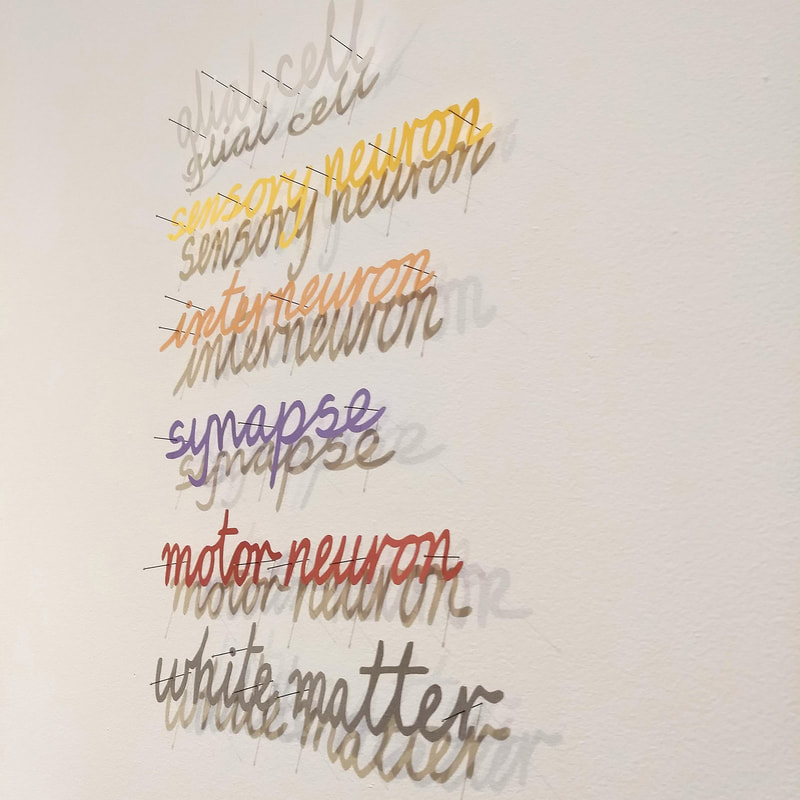

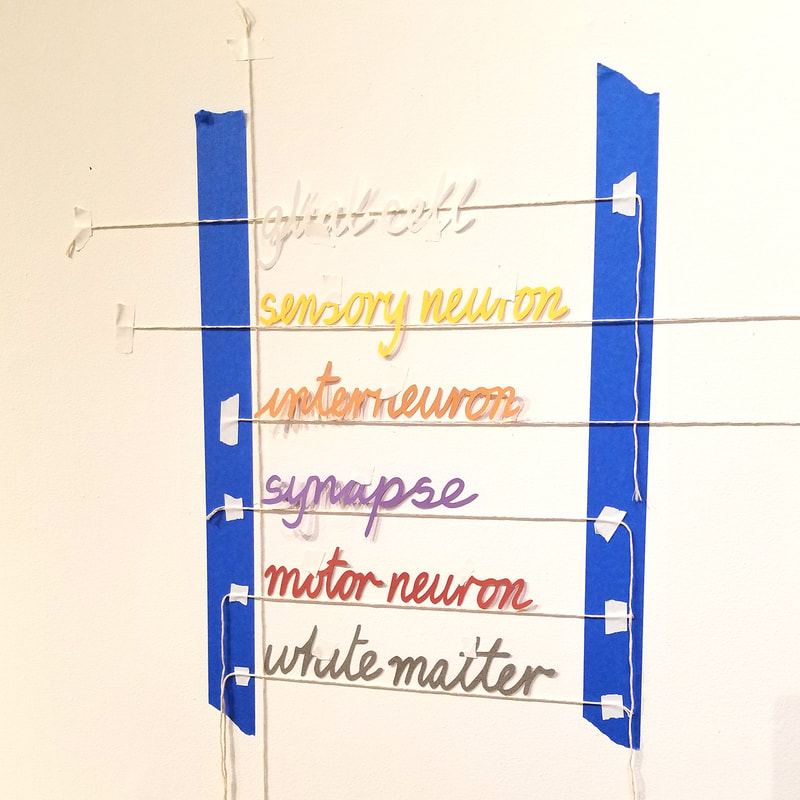

Fault Lines is a 15' wide installation. It consists of an embroidered xray, a paper and pin installation of a spinal cord cross-section measuring 8' across and 5.5' tall, and a color key. Created to understand research by the Pfaff Lab at Salk Institute in La Jolla, CA, Fault Lines delves into the physical nature of our bodies at a neuronal level.

The spinal cord starts at the base of the brain and runs through the spinal column. At any cross-section, it can teem with activity. Neurons communicating via synapse are responsible for sensation, pain perception, proprioception, movement, and the voluntary and involuntary dance of organs.

The layering of paper shapes and forms to represent the white and grey matter of the cord builds a narrative of symmetry and repetition while the colors point to function and interaction. Enlarging the cross-section of the spinal cord around 200 times, we can highlight the various regions (in broad strokes), showcasing the different categories of neurons, as well as tell a visual story about motor neuron disease.

Loss of a significant number of motor neurons changes a body. When I talked to Dr. Samuel Pfaff from the Salk Institute about how the polio virus invades the motor neurons in the spinal cord, he explained that the motor neuron has a receptor which the virus attaches itself to enter the cell body. Multiplying within the cell body, the virus destroys the neuron from within. PhD students Peter Osseward and Ben Temple from the Pfaff Laboratory have been instrumental in my understanding of how neural messaging within and beyond the spinal cord responds and activates muscles, sensation, and movement. Working with the lab has helped to answer the fundamental question of how my disability came into being.

The layering of paper shapes and forms to represent the white and grey matter of the cord builds a narrative of symmetry and repetition while the colors point to function and interaction. Enlarging the cross-section of the spinal cord around 200 times, we can highlight the various regions (in broad strokes), showcasing the different categories of neurons, as well as tell a visual story about motor neuron disease.

Loss of a significant number of motor neurons changes a body. When I talked to Dr. Samuel Pfaff from the Salk Institute about how the polio virus invades the motor neurons in the spinal cord, he explained that the motor neuron has a receptor which the virus attaches itself to enter the cell body. Multiplying within the cell body, the virus destroys the neuron from within. PhD students Peter Osseward and Ben Temple from the Pfaff Laboratory have been instrumental in my understanding of how neural messaging within and beyond the spinal cord responds and activates muscles, sensation, and movement. Working with the lab has helped to answer the fundamental question of how my disability came into being.